- One counterintuitive issue with spaced repetition is that the modern algorithms like FSRS are actually almost too good at scheduling. The effect is that each card is almost perfectly scheduled to be very difficult but still doable. Now, it's a bit weird to call it an issue considering it's the whole concept working exactly as designed. But it does cause one follow-up problem.

The problem is that in life, we are accustomed to things becoming easier as we get better at them. So you start drawing faces and it starts out feeling very difficult, but then as you practice more and more, it feels easier and easier. Of course, by the time it's feeling easy, it means that you're no longer actually getting effective practice. But nevertheless, it's the feeling that we are accustomed to. It's how we know we're getting better.

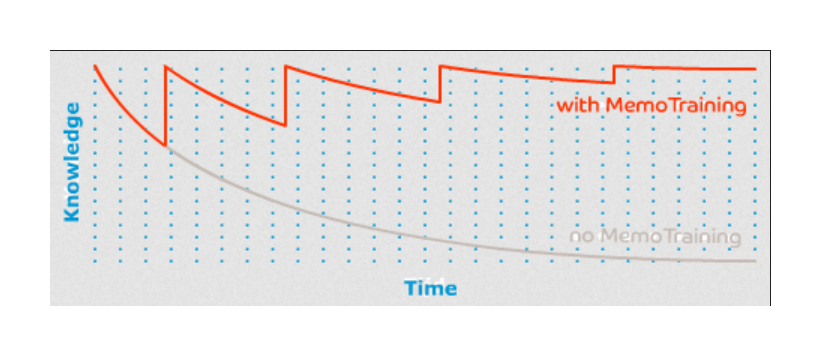

Because spaced repetition is so good at always giving you things that you will find difficult, it doesn't actually feel like you're getting better overall even though you are. The things that you are good at are hidden from you and the things that you are bad at are shown to you. The result is a constant level of difficulty, rather than the traditional decreasing level of difficulty.

I've encountered this problem myself. I built a language learning app for fun, and some of my users feel like they're not learning very much compared to alternatives that don't use spaced repetition. In fact, it's the exact opposite. They learn much more quickly with mine, but they don't have that satisfying feeling of the lessons becoming easy. (Because if I gave them easy challenges, it wouldn't be as productive!)

I'm not sure what the best way to solve this problem is. I would much appreciate any advice.

- >I like Mnemosyne (homepage) myself - Free, packaged for Ubuntu Linux

It seems to use a 2 decade old modification of a now 4 decades old algorithm which will be worse and waste more of the user's time than using Anki with FSRS or SuperMemo with SM-18.

- While I’ve been working on my knowledge base meets spaced repetition project, I looked through a bunch of articles, and it’s very easy in fact.

We keep forgetting stuff. But we can remember it more by active recalling. And there is an evidence that you can recall with intervals that grow, to make it optimal. That’s it really. Everything else is tooling on top of that simple fact.

- Unfortunately seems to be too old to include coverage of FSRS and the associated optimization algorithms. Would love to see Gwern’s updated thoughts on this.

- Anecdotally I stumbled upon this phenomenon when trying to learn how to play the piano. I noticed that at the end of a session I make so many mistakes and feel like I didn't learn that much, but coming back to it after a day or two I really felt the difference.

- Really big fan of the design of the header on this blog, cool way to represent tags and article information without it being monotonous.

- There are three closely related reasons why spaced repetition is much less useful in practice then in theory.

1. It doesn't train real task performance. There is a spectrum of problems that people solve. On one end it is the recall of randomized facts in a flashcard prompt->answer way. On the other end is task performance, which can be more formally thought of as finding a path through a state space to reach some goal. The prompt->answer end is what SR systems relentlessly drill you at.

2. SR is pretty costly, prompt->answer problems are also low value. If you think about real world scenarios, its unlikely that you will come across a specific prompt->answer question. And if you do, the cost of looking it up is usually low.

3. The structure of knowledge stored is very different (and worse). If you think about high performance on a real world task like programming or theorem proving, you don't recall lists of facts to solve it. There's a lot about state space exploration, utilising principles of the game, leveraging known theorems, and so on.

This is a more descriptive version of the "rote memorization" argument. There's two common counters to this:

1. Learning is memorization. This is strictly true, but the prompt->answer way of learning is a specific kind of memorization. There's a correlation-causation fallacy here - high performers trained in other ways can answer prompts really well, it doesn't mean answering prompts really well means you will becoming high performing.

2. Memorization is a part of high performance, and SR is the optimal way to learn it. This is generally true, but in many cases the memorization part is often very small.

These ideas more accurately predict how SR is only significantly better in specific cases where the value of prompt-answer recall is really high. This is a function of both the cost to failing to remember and the structure of knowledge. So medical exams, where you can't look things up and is tested a lot as prompt->recalls, SR finds a lot of use.

My own guess for the what the next generation of learning systems that will be an order of magnitude more powerful will look like this:

1. Domain specific. You won't have a general system you chuck everything in. Instead you will have systems which are built differently to each task, but on the similar principles (which are explained below).

2. Computation instead of recall - the fundamental unit of "work" will shift from recalling the answer to a prompt to making a move in some state space. This can be taking a step in a proof, making a move in chess, writing a function, etc.

3. Optimise for first principles understanding of the state space. A state space is a massive, often exponential tree. Human minds cannot realistically solve anything in it, if not for our ability to find principles and generalise them to huge swaths of the state space. This is closely related to meta-cognition, you want to be thinking about solving as much has solving specific instances of a task.

4. Engineered for state space exploration - a huge and underdeveloped ability of machines is to help humans track the massive state space explorations, and evaluate and feedback to the user. The most common used form of this is currently git + testing suites. A future learning system could have a git like system to keep track of multiple branches that are possible solutions, and the UX features to evaluate various results of each branch.

- This is memorization. There is debate on if that is learning. At the very least you need to apply this learning to real life or you will never know if you learned. So get to that point quick.